I don’t get to choose

I don’t choose what I paint or how I paint it. Sounds odd. Let me explain.

What I mean is that I don’t sit down and decide, “I will paint how I feel about the river—and I will use these colours and this kind of brushstroke.” I’ve tried being dictatorial like that and it just doesn’t work. The results are flat and lifeless.

What I paint has to come from somewhere deeper.

My decisions in front of a wooden panel come from my gut. Some might call it instinct or feeling, but I think it’s more holistic than either of those terms suggest.

For me the drawing, the colours—when things are going well—come from subtle impulses and quick yes/no responses. They aren’t considered or thought out, but they aren’t passing emotions or physical gestures either. In order to catch these impulses, I need to be in a receptive state—relaxed, exploratory and open. I can’t be worried about results or when I’m going to take a break.

Where does that yes/no come from?

All my life I’ve been looking at things and responding to them. So have you. Some impressions land deeply and become part of our particular set of affinities.

I’m drawn to sinuous, twisting forms like roots and rivers. That’s what I doodled in my school notebooks. No wonder I was attracted to Art Nouveau and Beardsley as a kid. In a poetry book we had I fell for William Blake’s fantastic interweaving of story, plants, creatures, and words. In an incredibly sexist book aimed at girls (this was the early 1970s) I discovered Turner’s incredible mists of colour and light.

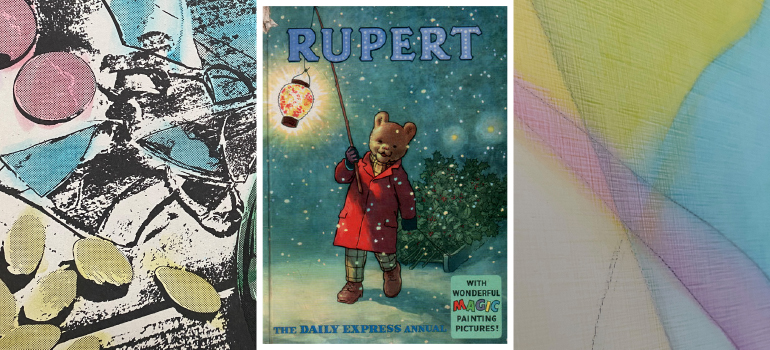

Another key visual experience came from the Rupert annuals my granny sent from the UK. You wet a brush (or your finger if you were wildly impatient like me!) and the dots turned colours and bled into the paper and over printed lines (see photo at top). Similar effects in my own paintings make my brain light up and bring me back to that sense of discovery and wonder we are so in touch with as children.

Innate and cultivated

So when my gut says yes or no, I think it’s informed by all my likes and dislikes. Some of them seem to be innate and deeply meaningful. Then there’s the question of exposure and cultivation. What’s part of my nature and what’s learned? If I hadn’t seen Turner’s work when I was young and impressionable would my colour preferences be different? And of course, some are temporary preferences that come and go.

And, in my case, any visual decisions I make are also informed by over 25 years of work with composition and colour as a graphic designer. It’s education and experiential information held so deeply that it’s part of me. I don’t need to think about compositional rules, Golden Sections, or colour theory. They’re just in me.

You’d think our visual language would be in us too. It is, but it gets covered over by what we think we should do, things we see others do, as well as fear and tension—all the usual things that get in our way.

A couple of years ago I spent months working on exercises and experimenting. I was searching for something that wasn’t far away, but was nonethless hard to find. (See my blog post Working without expectation). I took a break from shows and focused on finding my particular way of creating. I didn’t go into the project thinking I’d uncover my visual language, but it definitely one of the outcomes. It was invaluable work that I often reflect on.

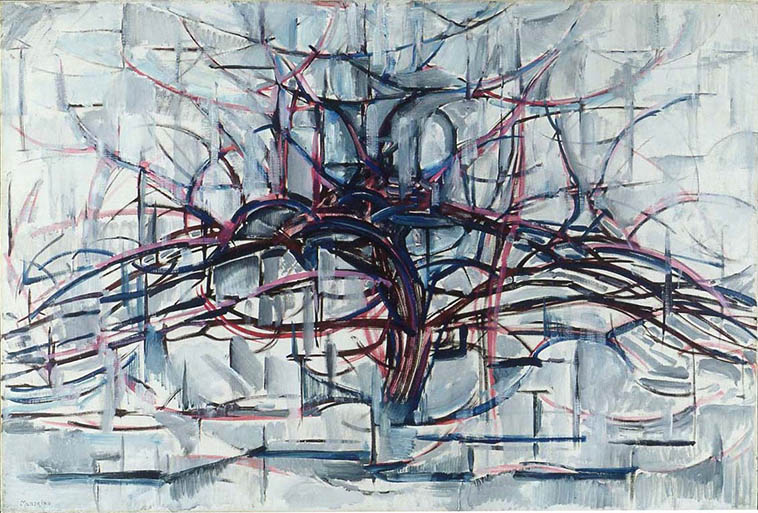

Horizontal Tree, Piet Mondrian, 1911

Art I grew up with

I actively disliked most of the reproductions on the walls of my childhood home. The Pisarro over our fireplace left me cold, and I loathed the Mondrian tree my mother adored (I always sat with my back to it in our dining room). But over time I started to discover art I responded to.

From reading some of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience, I discovered plates of his work at the library. I loved the washes of colour and the wandering vines. And the Van Gogh irises in my parent’s bedroom always seemed strangely alive as if they were in motion.

I was free of concern about an artist’s reputation or standing. I responded to what I saw and felt. And I was fortunate that noone at home tried to influence me one way or another. My mother loved that Mondrian tree and she respected my reaction enough to change the seating plan (but not enough to take it down!).

It’s an interesting exercise—to dig up art you were exposed to as a kid. Even the work I didn’t like was revealing and the whole exercise was a bit nostalgic. I collected mine in a Pinterest board.

Now I find myself drawing lines that echo what I am attracted to in the world—the sinuous forms of roots and leaves, flowing water, the twists and turns of a life. And I’m very clear about what I’m looking for in colour—luminosity and a prismatic kind of complexity. Which reminds me of Turner and Blake—childhood influences on my visual language.

Back to the river

Right now, my love of the river, of water, of wandering and swimming through the local landscape has begun to appear in my work. It’s been brewing for a while.

And I’m actively encouraging this work with immersion—by writing about it, walking by the river, sketching, studying the paintings I create—and letting it all lead me where it will. I can’t decide exactly what I want to paint, but I can set the stage, listen to my impulses, and see where they lead.

Top image: an example of magic dot printing, a Rupert annual, detail from one of my paintings in progress

Stay in touch

Sign up for first access to new work

(and never miss a blog post)

Hi Lindsay:

It seems we all kind of work the same way. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. I did a stream of consciousness yesterday, thinking of writing a blog. Yours is very strong and well written. I still need to go to the links.

Hope I see you in Muskoka at the spring show. The gallery is lovely. I just saw it yesterday.

Thanks for reading Cherie. I’m getting a lot out of writing the blog posts. Forces me to get clearer about things. Yes, the new space is gorgeous! Hope to see you there.